Courtesy of E.Z. Rinsky.

E.Z. Rinsky is an American-raised Israeli novelist. His two previous books, Palindrome and The Binding, were published by Harper Collins. His new novel is called Daughters of January.

Ephy: So, what’s this all about?

Ashley: The idea is that people who are doing creative things, the ones I know at least, are doing it because of the meaning it gives to their lives and the lives of people they know. It means something that they do this kind of work when they’re all fully aware they could do other things with those hours, that could be more lucrative, more relaxing, or whatever. But we continue to do this work because it’s important.

So, that’s the idea behind The Meaning Creators. But, let’s hear about you. What’s your name? What do you do?

Ephy: Ephy Rinsky. Rabbis call me Ephraim. Parents call me Ephram.

Ashley: Readers call you?

Ephy: E.Z. Rinsky. I’m a writer. I wouldn’t say I’m a mystery writer, even though my first two books were mysteries. But the next book is not a mystery. And I do other things, including a day job at a tech company here in Israel. And I’m a musician.

Ashley: So you’re an American in Israel. Or maybe an Israeli that used to be an American. How did you get here? Why did you get here? And why did you want to be a mystery—or whatever-you’re-becoming kind of writer—in Israel?

Ephy: I think the two things are kind of unrelated. I always knew I wanted to live here. About four and a half years ago, the timing was good. I was teaching economics and statistics at CUNY in New York and my contract was running out.

Ashley: How did you get to that, as a musician-writer?

Ephy: I originally thought I wanted to be a banker – one of those assholes – so I got an MA in economics.

Ashley: What made you want to be an asshole banker? Not, mind you, that bankers have to be assholes. In fact, I just had a conversation about this with a friend, that most people in banking are just miserable, a few are sharks, and a few have a real passion for it. So what did it for you? What put you on an “asshole path”?

Ephy: I got into economics in high school. I really like the puzzle solving aspect of economics and finance — and still do. I’ve always liked numbers, and always found it fun. But when I realized what the natural progression of that really looks like, it’s not like getting to solve fun puzzles all day. It’s 70hour weeks, cut throat, and money. It’s all about money. So just after I finished the masters I realized I didn’t want that.

Ashley: What was the transition to writing? Where did that come from?

Ephy: I was always into writing. I wrote for my high school paper. And I read a lot as a kid. My real first love was sci-fi.

Ashley: Give us some names.

Ephy: Asimov was my favorite. I really liked Douglas Adams, still do. Orson Scott Card. Margaret Atwood. Arthur C. Clarke. Lots of other stuff, but that was my passion. I wasn’t serious about writing till I was around 22 years old. I don’t want to get into this whole story—

Ashley: Well, now we’re going to get into it.

Ephy: After this master’s degree I had a quarter-life crisis and for a half year I was a street performer. I was this one-man-band on the street. Anyways, I was reading some crappy book at that time—I was reading some great books as well—and figured if he can do it I can.

Ashley: What were the great books you were reading?

Ephy: Confederacy of Dunces, or at least ⅞ of it, until I put it in the wash.

Ashley: There’s something appropriate about that.

Ephy: Yeah ,there is. And I was reading David Foster Wallace, A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again. So I wrote a book about street performing and moved to New York from Boston to get that published. And I ended up in New York for five years, where I wrote three manuscripts that didn’t get published until I wrote Palindrome, which was the first one that did.

Ashley: I’m reading Palindrome. There’s that preface where a woman is on a chair tied up. It was a white-knuckle scene. A really gripping moment. Where did it come from? Is it a series? Are you still connected to it?

Ephy: There’s two books, the second is called The Binding, with the same protagonist. At one point I had a third one outlined, but I got interested in other things.

Ashley: What were those other things?

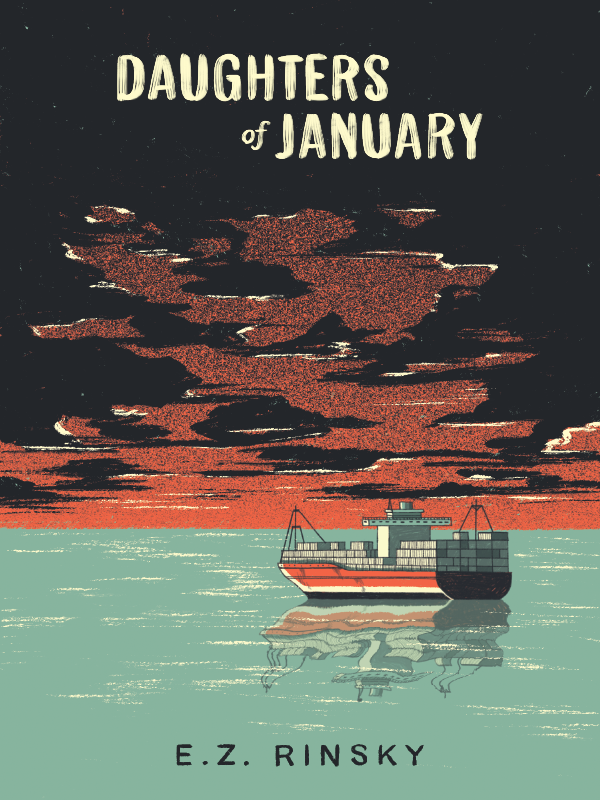

Ephy: I’ve just completed a manuscript, which is actually timely, given what’s going on in the world. It’s about a pandemic that kills everybody except for 11 people, who survive on a cargo ship in the middle of the Atlantic.

Ashley: Wow. Okay. That’s a premise. I’m guessing you’re getting some interest in that.

Courtesy of E.Z. Rinsky

Ephy: Yeah, I am. But sometimes I put myself in the publishers’ shoes and wonder if readers really want to hear more about a pandemic.

Ashley: That’s a good point. I think the truth is no one really knows what readers want, or what they’ll like. Especially right now, when everyone is asking, do readers want to hear about this? Will the noise of everything else going on drown out news of a book? But no one really knows. And that’s with all books.

Nobody ever knows, whether it’s a Donna Tartt book doing really well, when the previous one didn’t do that well, and the one before that was an enormous hit. And no one ever knows when it’s a major writer whose books falls with a thud, or when an unknown writer’s book goes completely explosive, viral, in the culture.

Ephy: No pun intended.

Ashley: Ha. Yeah, but we’ll only ever know when the book is out there. And publishers don’t know more than we do. They just have to pretend that they do. And I think most of them acknowledge it, at least deep down inside, that it’s not a science, no matter how much we want to make it one.

Ashley: So, back to your new book. You’ve got 11 people on a ship. They’re the last people on earth. Now what? How do you, as the writer, move that plot?

Ephy: The idea is that the world was wiped out sort of deliberately by a kind of eco-terrorist organization that felt the world was just fucked up beyond repair, and that humanity needed a second chance. Sort of a Noah’s Ark story.

The people on the ship do have some possibility of survival. And the real story is that these people have a second chance, but what does it look like? They’ve all taken this baggage from the old world and they’re all tainted by that past. So maybe they can’t really start over.

Ashley: And why the number 11?

Ephy: I wish there’s more significance. But I listed all the characters I wanted on there and that’s what came out.

Ashley: It sounds like a lot of characters to manage. That’s a big cast.

Ephy: It is a lot. That was the hardest part about writing this book. Palindrome and The Binding were all first-person with a single protagonist. This is essentially 11 protagonists, each going back with their own points of view. It’s tricky but at the same time there’s no one -- literally, on earth -- aside from those people.

Ashley: Was the Noah’s Ark metaphor deliberate, or was it a product of the premise?

Ephy: There’s a lot of deliberate biblical allusions but the Noah’s Ark is among the less intentional. It was more unavoidable. The bigger issues around religion in the book are questions like whether religion is something we should leave behind, or keep going?

Ashley: What’s its title?

Ephy: It’s called Daughters of January, which is the name of the terror group in the book.

Ashley: So let’s come back to Israel. You said life is better for you here. How so?

Ephy: I’m happier here. The quality of life is generally better. Work-life balance is definitely better. My parents also moved here, before me. I know that it’s true for everyone, but especially me, that our mindsets are connected to our geography. And in New York I found it very difficult to get out of the climbing mentality, in every facet – professionally, socially, financially. Here in Israel, I feel it’s less part of the culture and less a part of me. And I like that a lot.

Ashley: It’s like an orientation thing. Kafka spoke about that - having an orientation in life. The vertically oriented want to be up, so they can look down. The horizontally oriented life is much more biblical, in a way, because you’re not standing in point in time looking up and down, but looking out over an expanse of time that stretches deep into the past. And with the flood, it’s the same thing. Because the flood eradicated all verticality, to make everything horizontal. The mabul (flood) was a horizontalization of life. Ego raises us up. And that was possibly the issue with Noah’s generation – putting the self above all else.

When I think of what’s happening today, I won’t say the moral (which sounds too puritanical) but the teaching we can take is looking at our Golden Calf. We, today, worship the god of cheap crap. Of stuff. Junk. We borrow to buy more junk. Because it makes us feel good. And that self-centered need, of how I feel, has gotten us to this point.

Ephy: Yeah, when I’ve been thinking about this situation it’s terrifying, but it’s also elucidated a lot of things, made them concrete. Like the tradeoffs between freedom and control. We’re all isolating, and I think we all agree it makes sense to save lives, but at some point obviously none of us would be okay isolating for five years to save lives.

In economics, we have a monetary value for human life, which every organization has to come up with. We’re trading economic value for health reasons. But we have to ask the questions about how many lost jobs is worth one death. It’s insane that we’re having to actually ask these questions – and if we had a competent leader of the free world, he or she would be grappling with this stuff. But as individuals, these philosophical debates have hit home. Do I go out for a cup of coffee? Is the cost to my mental health of not going out worth the infinitesimal chance of killing someone? What’s the risk of leaving my house on a normal day?

Ashley: Yes, and we all drive to work everyday, or most of us do. And that’s the greatest risk most of us will take in our lives, statistically. And we take it every day. But we’re also facing other ethical scenarios. All of a sudden the Trolley Thought Experiment are becoming horrifyingly real.

As a religious person, when I think about the Torah, and the sanctity of life, I think about that fundamental principle. The sanctity of life. The value of life, regardless of productivity, or other considerations. But still, decisions have to be made. I can talk about the sanctity of life, but the doctors are out there making those calls.

Ephy: This sounds like an enormous amount of hubris, what I’m about to say. I have a streak for the fatalistic, which is why I wanted to write the dystopian stuff. This one finally seems like something that’s aligning with my expectation of the worst case scenario. I’ve finally prognosticated it accurately. And I feel like I’ve been ahead of it, by a week or two, even those that’s really hubristic.

Ashley: I don’t think it’s hubris. I think it’s people who live with a certain mindset, a certain anxiety, speaking for myself. When you get used to living with angst for a long, long time you start to see how things can unfold, and that becomes an expectation inside.

So when this all started, early February, for sure, I was telling my wife when you go to the grocery store buy extra latex gloves, buy extra food. That was two months ago. And she wasn’t really taking it seriously. But I noticed this pattern from myself, that with people who live with a lot of anxiety, when the crisis comes they can sometimes become very calm, relatively to the rest of the society, because they’re used to the feeling. It doesn’t feel that different from daily, life, even if the volume is a little turned up.

I was once stuck in a coup in Honduras, in a 24 hour a day curfew. You could not leave the hotel. The coup was happening on our street. And I never felt so calm. I went onto the balcony, and they were shooting tear gas down , and I meditated out there. But that’s what I think it is. People get used to that feeling.

Ashley: Before we wrap this up, the question I want to ask is what does it mean to you to be a writer? What does it mean to you, and also to the people around you, and your readers?

Ephy: For me, it’s almost like eating or drinking or using the bathroom. It’s a part of my daily life which I have to have. If I miss a day of writing I’m in a foul mood all day. That’s on a basic level. I’ve been on a routine so long of six mornings a week of writing, that by now that’s why my day exists. If I had to guess why I do this so compulsively, I think in one way it’s a form of self-therapy. I’m not writing anything remotely therapeutic, but —and I’m sure this sounds familiar to you as a writer as well – accurately portraying the things in your head is a deeply cathartic experience.

My dad, who is religious, would say that you’re becoming a vessel, when you get it right. You’re channeling something. And maybe by this point, I’ve done it so long it’s just an absolute necessity for me.

What it means for people around me -- I don’t know. People like my books. People really enjoyed and had a lot of fun reading them. But I don’t think they’re the kind of books people would say, that changed my life.

Ashley: Is that the kind of book you want to write? Is that important to you?

Ephy: That’s a good question. If I could hear people say anything describing a book of mine, I think probably what I’m going for is “You made me think about something really interesting.” I don’t know why -- and I’d probably need a couple hours with a therapist to get to the root fo what I really want people to say when they read my books. I definitely want them to say it was funny. Even the mystery books, I want people to find them a little funny.

I’m not sure what it means to my readers. I don’t think it means so much to them, at least not so far. People are always saying, “Wow I wish I could have your discipline.” And I’m shocked when they say this since outside of my writing I’m one of the least disciplined people I know. I can’t even keep my kitchen clean. It’s like I use up all my discipline in my writing, and have none left over for anything else.

Ashley: It seems like you and they are speaking two different languages. They’re saying, “I wish I could have your discipline.” But you’re saying, “You mean, you wish you could have my obsession.” Because when you build your life around one thing, that’s an obsession. It’s not a bad thing. If you know about David Goggins, the ultra-endurance athlete, who talks a lot about motivation. He says if you’re using motivation in your life to do something hard, you will fail because the motivation will run out. He says, you have to be obsessed. If you’re obsessed, if you build your life around it, then you can keep going no matter what happens.

I think that’s what people hear. For you, you’re satisfying your crazy desire. It’s like a drug dependency, an intellectual dependency. But it requires balance, otherwise it consumes.

Ephy: I have quite an addictive personality. It could have easily been something other than writing.

Ashley: We were just watching Uncut Gems.

Ephy: I love that. He’s incredible, isn’t he?

Ashley: Yeah, I’ve always loved him. He does these great movies, like Punch Drunk Love, but then he does these insanely ridiculous movies, like the one he did with Al Pacino. I just feel he’s not laughing with us, when he does those movies. He’s laughing at us. He’s laughing at the people who got to watch them. That’s my theory. There’s no other explanation for making something that bad than he’s just making fun of us.

Ephy, thanks for doing this. And keep us up to date about developments with Daughters of January. I know a lot of The Meaning Creators fans will be eager to read it.

Ephy: I will do that. It was a pleasure talking.

Join the conversation.