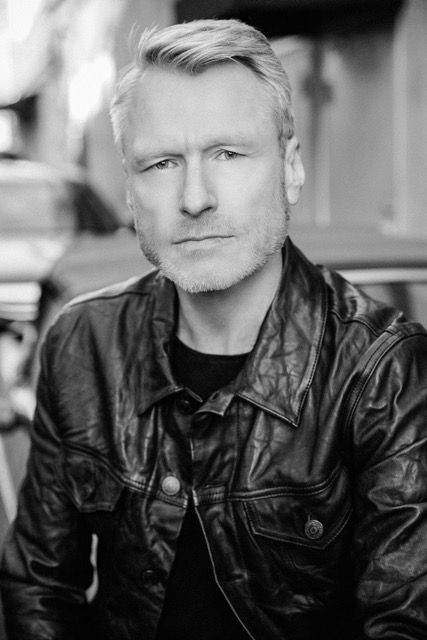

David Francis, based in Los Angeles, is the author of The Great Inland Sea, published to acclaim as Agapanthus Tango in seven countries, Stray Dog Winter, Book of the Year in The Advocate, winner of the American Library Association Barbara Gittings Prize for Literature and a LAMBDA Literary Award Finalist, and most recently Wedding Bush Road published by Counterpoint Press in 2018. His short fiction and articles have appeared in publications including HarvardReview, The Sydney Morning Herald, Southern California Review, Best Australian Stories, Australian Love Stories, Los Angeles Times and The Rattling Wall. His book and film reviews have appeared in publications including Los Angeles Review of Books and The Advocate. Film rights to The Great Inland Sea and Stray Dog Winter have been optioned in France and the United States, respectively. David began his legal career in 1983 with Allens, an international law firm based in Australia, and recently retired from the Los Angeles office of the London-based firm, Norton Rose Fulbright. He is Chair of PEN America in Los Angeles and a board member of PEN International.

For more information go to www.davidfranciswriter.com.

Listen to the episode on your favorite podcast site:

Apple Podcast: https://apple.co/3rjazlM

Spotify: https://spoti.fi/3gnl3Kk

Amazon Music: https://amzn.to/34vt916

iHeartRadio:https://ihr.fm/35L0OED

Ashley Rindsberg: So David Francis, thank you so much for joining me here on The Burning Castle Podcast. For anyone who can't see David, he is in the most classic of all writers Garrets up in an attic. So I won't fillabuster at the beginning of the, of this episode. I'll turn it over to you, David, just to give a little bit more background than, than the formal introduction that we just heard.

Tell us just the basics, the fundamentals about who you are and what you do.

David Francis: Well, I'm essentially a kid from the country in Australia. Where I've just returned from the farm where I grew up that my sister now runs, which is kind of a whole situation. And I grew up doing that and I rode show jumping horses, which is an odd kind of sport for Australia internationally in the seventies and eighties.

And and then I was, I'm a lawyer by trade and I've recently retired from a law firm called Norton rose Fulbright, which is a big international firm where I did public finance, which is financing schools and hospitals and universities. I started writing in the maybe mid nineties. And my first novel came out in the early two thousands and I have three novels in the world and a new one that I recently finished and, I am involved with Penn international the freedom of expression organization, which I'm defense writers throughout the world. And I'm on the board of Penn international and I've also been involved with Pan America here in the states and I'm currently in LA, in Hollywood, looking out my attic window into the rain, into the Hollywood Hills and delighted to be here with you Ashley.

Ashley Rindsberg: Thank you. So, you know, I've got a few questions, a big one is, how and why you got into writing as someone who is trained in law, who had what sounds like by all measures, a very successful career in that field. And there's sort of a, sort of this intersection of two questions that I have, but at the heart of it is the question of why. Why would anyone want to be a writer? It's a question that I ask myself every day. Struggling in this field that is so filled with struggle and with some of the stories of the most successful by literary standards are those who struggled the hardest and we've kind of lionized, we've made myths of Dostoevsky or whoever working his fingers to the bone in Siberia in order to carry out this noble craft of his.

So why did you do it? Why do you do it?

David Francis: Growing up in the boonies in Australia, I always secretly wanted to be a writer. I don't know. I don't know why I didn't study journalism or creative writing. Not that, was really on the radar. I studied law because it was a way to make a living. I was never passionate about it. What I was passionate or passionate about was the sport I did. And so I accidentally became a lawyer and worked for a firm in Australia and then got on a team to ride jumping horses in, Europe and then washed up here in the states. So I, I never loved being a lawyer and I always used it as a vehicle to be able to afford to do other things.

And the gift of that has allowed me to afford to write what I like, what I want to write, what I'm passionate about and not really be a gun for hire. So I, I have written strange, somewhat unusual fiction that I have, have loved doing. And so I fought for the time to write as a lawyer. And when I got that window where I was able to, I was usually in, in a place where my subconscious mind had been preparing me to to put something on a page. And I'm grateful for that. It's only now having retired from the law that I'm doing some editing work, where I'm working with other writers and but still doing my own stuff. So I still have a passion about writing fiction and I don't resent it. And it's, it seems to me kind of, hate the word gift, but it's a gift for me to be able to, to do that and pursue that in, in whatever way it unfolds.

Ashley Rindsberg: It's an interesting model or the one, the one that you pursued it's you know, it's, you're, you're by no means the, a solitary figure. Who's kind of went down that path of a profession, to pay the bills to more than pay the bills, to establish, establish a livelihood, a life something that will carry you through and support the art. You know, it's I think of Trollope Anthony Trollope I'm reading right now, who was postmaster general of England within, you know, pre United Kingdom and wrote in the mornings and did it religiously and was prolific. You know, in my opinion, genius, or more recently Amor Towles who was, I believe in an investment bank or it might've been private equity, but I think in an investment banker who was sort of a bit of a wunderkind in fiction left fiction to go into banking and finance and then sort of returned to fiction more recently after a 30 year long career And it's a very interesting pathway, but I imagine, and I've been on that pathway myself.

In some regard I would say probably less successful than, some others, including you in both tracks and both the fiction and the professional track, but it comes with a certain amount of hardship. I would imagine. I felt, I feel that it comes with a certain kind of tension that you are doing this other thing in your life that you don't fully believe in and you don't fully trust. Is, is that something you experienced? And if it is, how did you deal with that tension if you felt it?

David Francis: I think that pursuing career that isn't a passion does take an emotional toll and over, you know, I did that for three decades and what I was eventually able to do is create a gig where I had some flexibility. I came in originally taking a fair amount of time away to do a sport. And then I morphed that into taking a fair time away to travel doing writers' retreats and I would write. You know, I took would take a month off and go to the, there was a place called Portland Castle in Scotland, where I got a fellowship and I did six months in Paris at the where I go to an Australian writing residency. So I was, I was paid less than I was worth to the law firm, but they charged me out at a pretty high rate. So I was able to establish an equation that kind of gave me some flexibility. And so it wasn't quite soul destroying as that otherwise might've been, but still it took its toll. I weirdly was able to switch even in my office from drafting documents and then going into the world of my fiction quite readily.

And I don't know whether that's a function some kind of ADHD or something, but I, I do remember my first novel my boss who was quite supportive, I will say suggest it should be called "On Company Time" was her suggested topic because it was kind of known that I had this other life and that I, you know, that I was pursuing it. And that was my real passion. Without the writing. I don't think I could have ever done that. And I'd also add that I did this sport that was highly adrenalized sounds like a very American word, but there was a lot of adrenaline involved and sort of expectation and disappointment and traveling. And I would jump on a plane and go to PalmBeach in Florida and I was sponsored and would ride these horses and come back.

And that world I didn't sleep. And it was, there was a lot of danger involved and then I got to a space where actually I was in therapy and my therapist asked, you know, what are you truly, what's your true passion, if you want it to be a little bit still. And and that was writing. And so I, I got brave enough to do that. You know, terrified that I wouldn't be. Wouldn't be good. You know, whether I'm good or not, that's what I need and want to do with my life.

Ashley Rindsberg: So that first novel it's, it sounds like you're already into your law career at that point. And how did it happen? How did you, where did the seed come from? How did you except that this was the particular pathway because writing can take many forms. It could have been in stories. It could have been a poem, poetry, it could have been any, any number of things. Memoir. You chose a novel, which in my mind, and in my experience, my personal experience, it's the most difficult choice I've done various kinds of writing, a novel sucks.

You dry and then some, so how did you get to that point and how did you grapple with it? Was it a natural choice? Did you have to come to terms? What was it like and how did you come to the idea for what this novel would be about and what it would be in the world?

David Francis: I didn't consciously choose that genre. I just started writing and it emanated originally from when I was maybe 19, I was at law school in Australia and I worked with horses about 70 miles from my law school. Then my grandmother had gone blind and lived in a facility. She was 98. And I would visit her every day between my horse farm job and law school and sit with her.

And she had grown up in the Outback of Australia in the 1880s. Her mother was from Salzburg in Austria and her father was affectless Scott had. It's funny. I haven't told this story for such a long time, but he met her when she was singing as a young opera singer in Vienna and swept her off her feet and took her to the Outback of Australia to a place that was a hundred square miles in the middle of nowhere. And she had these kids in this mud brick house and the Aboriginal tribes warring at the bottom of the garden. So my grandmother told me these stories and I, I wrote them down and thought one day, I would like to write about this. And so it wasn't, you know, for another 20 something years or 20 years that I, I started playing with that idea and I got into a writing with a writer called Les Plesko who was a really great novelist and editor under published, but had a a following here. And I was told that if, if he likes your work, he he'll invite you to his private workshop. And I think I probably would have written myself into oblivion if I found myself there, but I wrote in a kind of organic fashion.

Yeah. Not knowing whether it was going to be stories or a novella or a short story or what, what it was going to be. But I was just writing this story in a very almost unconscious way. It was sort of flowing through me from, from general other generations of my family. It was kind of a bleed through and that, that great-grandmother whose story it's a little bit based on The sense was that she was Jewish and that she was had ended up in this very alien environment during the war. So I melded some of my experience and some of her experience and my grandmother's experience in what became agapanthus tango. And then just to add onto that, I sat with a woman at a, at a dinner party who represented a number of writers and directors and she's oddly pulled byhovens who just has a movie out called Benedetta that's about lesbian nuns in the 1300's. Anyway, I became friendly with her and I got brave enough eventually to tell her that I was writing something and I sent it to her and she sent it to an agent in London that she worked with. A week later, there was a bidding war for, in London with between Picador and then Fourth Estate HarperCollins, which was this amazing thing. I mean, it's sort of been all downhill since then, but that was sort of a miraculous confluence of events.

Ashley Rindsberg: How old were you at that time? Just out of just a place you in time

David Francis: probably 2000, I would have been early forties. Yeah.

Ashley Rindsberg: So that must have been, I mean, it's such an interesting thing to come into the two particularly fiction because usually people start very young in fiction when they succeed, they they're on that path or on a track, like in most pro careers and professions, they go to the school that MFA programs, and then they go to the journals and they get the edge agent and blah, blah, blah.

So this was quite a different path and I imagine that must've been a very validating experience to write the book that came from somewhere, not somewhere, almost genetic. And then to have it picked up in such a fashion really must have been something nourishing.

David Francis: It was, I mean, it was kind of extraordinary, but also it was weird because here I was with my life in the U S. and this book was published in various languages, published in Australia and Holland and Italy and Germany and France and the UK and elsewhere. And, but in America, it wasn't, it wasn't picked up for another five years. That that was, that was a strange experience. Yeah. Not to feel, I felt like I'm, I'm a writer, but I'm not a writer in America. So in my own life it, I didn't quite inhabited. It seemed like something that was happening far away. And yet on the strength of that, I was able to you know, I got this fellowship to Paris for six months where they, the Australian literature fund sends an Australian writer to this Garrett in, in the marae in Paris, which was amazing. And this whole, and I thought I'm never going to have to go back to law after this. I can't stand it. And I just, I just thought of how my novel got published in France was I had a foreign rights agent in London who sent this book to an editor at , which is a really good house in Paris.

And she had asked him if I was writing something else and that agent hadn't responded to her, but I had met someone in Paris. Who I'd given my card to that had the name of the novel on it and the cover of the novel on this card, he was a translator and he happened to be on the train with this editor, this French editor. And he opened his wallet and he, she saw that card and she was like, oh my God, I saw, I love that book. I heard back from them, nothing ever came in. And then by the end of that day, I had a publishing deal in eight months, which was like one of those weird serendipitous things.

Ashley Rindsberg: It's, you know, it's one, it's one of these things that it seems so serendipitous. It seems lucky, but I feel like there's also an element. Of some karmic element of luck where you're putting action into the world. You're putting energy into the world. You're at the dinner party. You're in Paris. You know, it wasn't blind luck. There was, there was some intention behind it. That was your doing that somehow something in the world reciprocated. So, you know, I feel like that's cause I think a lot of people hearing a story like that, it's like, well, why can't I just get lucky like that? But there's much more to it than that.

David Francis: I think that's really true. I think being someone who's bold enough to go and I mean, I think the sort of chutzpah behind the luck, there's this sort of being out in the world and meeting people and being able to talk about what you're doing and can making connections and allowing manifestation in a way with, with the kind of intention. Yeah. I think. Yeah, right.

Ashley Rindsberg: So you have the first novel out in the world, just not in your part of the world which is actually something I hear and I've paid attention to that. A friend of mine who's actually French was asking me if I've read, I can't even remember the name of the author. And I said, I haven't heard of this guy. And he was absolutely gobsmacked that I'd never heard of this world famous, it wasn't even a French author. I think he was a Italian Jewish author who is like the big guy in France that nobody in America has ever heard of. It's one of these weird things that just, you know, you, these weird angles of literature that something works in France has no appeal in the U S what works in the U S has no appeal. If some other place it's just the strange kind of array of international taste. For you, this was working and that, how does that roll into the next book and the next book after that?

How did you, was it just saying to yourself? Okay, great. Things are moving along. Let's think about the next idea or was it, you know, was there more to it than that?

David Francis: It's funny that you say the word “idea”. And this always sounds suspect, but I feel like I don't write from a conscious idea. I write, I write a scene that I see and allow it sort of organically to inform and unfold into the next scene. And if I, if I have this great idea, And I'm trying to write from A to B, I feel like I'm engineering a story that may want to go to Q, you know, and if I can get out of the way of my conscious engineering, loyally, structuring mind, something more original might emerge. And for my second novel, which I started, as I recall in, during that gig in Paris cause I'd finished my first book, then I started writing a story of a kid, a young guy, a young Australian artist who was heading to Moscow on a train from Prague. And I had done that when I was maybe 23 or something.

And it was still the Soviet era. And I'd taken photos out of the train window. Knowing that you weren't supposed to take photos of telecommunications or infrastructure, but I was taking pictures of horse-drawn hay cuts and women in the fields with sides and it felt very. Kind of Turgenev Rogan he wrote a book called "The Hunters Album" or the hunters tales or something that was very sort of rural Russia in the, in the 1800's and it felt very much like that. Anyway, I essentially got arrested when I landed in, in, in Moscow because I'd taken these photos and I was telling that story in a novel setting. And then I was also writing about a kid growing up in Australia and I had these two, what I thought might've been two different novels, one a sort of suspense, emotional love story. That was happening in, in Soviet Moscow at the end of and drop off early Chernenko very repressive time and this other Australian story, and they eventually married into what became "Straight Dog Winter" which was my second.

Ashley Rindsberg: It's a really interesting point to think about over-engineering a novel, you know, because I think along the spectrum of how someone could write a novel. On the one hand, you have something that's very free and free flowing structurally. And then on the extreme opposite end, you have something that's much closer to a crime novel crime fiction or thriller. That's very engineered and, you know, people try to put themselves somewhere along that spectrum or, or generally they go one side or the other. And I know that's something that I've grappled with, how to place myself and probably thinking too much about it because. You know, you start to think about the audience because you start to think about how is this ever going to sell, because you're thinking about how am I ever going to make a living doing this.

And that comes back to what you were talking about, having a career, which kind of, you know, has its own burdens, but frees you from that other thing where you don't need to calculate, how is this book going to earn me a living so I can live a decent lifestyle. Is that, is this something you feel like you gained from, from the path that you took?

David Francis: Yes. I believe it's certainly given me the freedom and it's not like, I mean, I've sold in various countries but it takes me five years to write a novel, the way I, that I work, so I could have lived off that nicely for a year. But amortized over five years, that's not a great living, but you use the word thinking. And I think thinking is maybe not always an asset, certainly for me, when I get into my thinking mind, I get out of my unconscious mind and if I write anything decent, it's usually in my half sleep longhand. When I first wake up in the morning. When I'm in that sort of dreamscape world. And I try and write from more from my body than from my mind, if that makes sense. I work with people and a bit, right. To introduce them to the work through meditation to try and get into that sort of sensory detail that what did they call it? The vivid continuous dream.

Ashley Rindsberg: That's the meditation gong digital era. So, so how does that work? How do you write from that place? How do you get to that place and how do you write from that place? Because as I, as I had just mentioned the writing that I have done. For the, for the novel that I wrote recently was very thought through planned out meticulous. And this is not, these are, these are not ways of praising myself. I'm not really sure that that was the best way. So how do you do it and how does it, and how do you know you're doing that in a way that makes sense?

David Francis: I believe I try to be, to inhabit my body and be in, the present in a way that I'm not distracted by the world as much and can begin to inhabit the story and dream around inside the story. And in my mind's eyes, see a room, see an expression smells. Get the details in a way that I'm not coming at it from the outside. I'm not imposing my intellectual mind on the story, but allowing it to emanate from a more organic place. And I learned that through that first novel, that was sort of bubbling up through my DNA, you know?

So it's a strange adventure. Takes a lot of getting out of my head and being, getting out of my head space that's trying to, trying to make sense of everything and control the narrative and trying to get it to where I think it's supposed to be. But just inhabiting a story and allowing it to unfold and trusting that I might be riding into some box canyon that I'll need to throw stuff away, but something in that work will inform something else and a sentence or a word. There's a book by a woman called Annie Dillard called "The Writing". Talks a lot about this as a way of writing, but as you say, if you're writing with a deadline or very specific goals or something Imposed it's a risky way to do it. And I, you know, I'm friends with Jane Smiley here in California. Who's a Pulitzer prize winning American writer, and she would never go leave the gate until she knew exactly where she was going. And now I was on with a panel once with Colm Tóibín, the wonderful Irish who lives in. And, and whose last name escapes me, who just won the Booker prize. And they would coming at this equation from two totally different perspectives, both wonderful writers. So I think it's a little bit how you're wired in the brain. And I think it's hard to become one if you're not, if you're the other, but I think you can meld those worlds. Somewhat. I also think that loyally structured mine works in the background without me being so aware of it, to provide some underlying structure. And so I think sort of some poet, some poets and writers that I know who live totally in the sort of the theory or with the world, it's harder for them to, to stay on a track working in that fashion.

Ashley Rindsberg: Yeah, that's interesting. It's a bit of a, it's a bit inverted from what you would normally think. You would think normally that it's the conscious mind driving the process and the unconscious mind shaping it in the background for you. It sounds it's a bit upside down, you know, from the rest of us, it's your unconscious mind leading the way and you see the conscious intentional piece that's kind of in the background, shaping things, putting scaffolding around it as you go. Very interesting.

David Francis: So. It's a matter of accessing that unconscious mind and that it's the tough, the tough, but most interesting part to me.

Ashley Rindsberg: You know, that's something that I loved so much about writers. Of the early 20th century, the surrealists Henry Miller and his big tomes and the rosy crucifixion. It's just this incredible, it's not even stream of conscious it's it's stream of unconscious. It's deeper than that it takes you along and you're somehow captured by it. It's the weirdest thing. It shouldn't really work, but it does. So w what are you, what are you doing now? You've retired from your law profession, from your, from your day job. What does that leave you? I mean, you. Working a job like that is very structured. It structures your time, especially with the law because you're billing hours. And now you're your interaction with time I'm assuming is a bit different. And also with the writing because of that, because you don't have that narrow kind of window to work and you've got more. So what does your day look like and what is the writing look like on account of that?

David Francis: My day is, is freer. I will admit that I have taken on some editing jobs where I'm editing novels for, for writers. And that gives me some structure and something just to go to that feels like work. But I've been getting up in the morning and getting on a meditation with a bunch of poets and then writing from a prompt Freehand and seeing where that takes us. And then we read whatever poems we've written. And that's a really interesting skill for me to write in the moment with these accomplished poets where, you know, that's not what I am. And we oddly just have a little collection that's come out just yesterday called Slow Lightning, impractical poetry that has grown out of that, that group, which is, which is a little.

I'm also very involved with PennInternational. So gettingwriters out of MiraMar and Afghanistan and Belarus. And so this protection of writers and writers as in prison for who have written politically in the wrong, you know, in the wrong part of the world. So I'm involved with that and freedom of expression. And as a lawyer, I help out that organization that's based in London. With some legal, legal stuff. And some of the more technical aspects of that sort of exercises, my legal mind a little bit. And I'm basically feeling free to write what I write and I'm writing a fourth novel. No, I'm not. I'm writing a fifth novel. And it's amazing to me that I could even imagine in my life that I would be thinking about writing a fifth novel. I mean, I guess I'm in my early sixties and time has passed, but to imagine that I would have a little group of books behind me is, is uh, is astonishing. So I'm writing a very Australian novel, having just finished a very LA novel. So a very contemporary LA novel which is now Looking for a new agent. Cause I feel like my existing agent wasn't really suited to this, this work. So I'm in the throws of that and just working on something new and having fun with it. And I meet with my writing group every week on zoom and we read our stuff to each other Janet Fitch, who's an American writer who wrote"White Oleander," which was a big book here. And so there's an Oprah book and sold in 20 something languages and and a film. Yeah. And Dylan Landis, who. A wonderful writer out of New York a short story writer mostly. And anyway, we read our stuff to each other and then we respond in the moment. And so that's a weekly practice that sort of keeps me nudging me forward. Like I need at some pages for the group. And then I have some responses from the group to keep me going. And just to follow up on what you said earlier. Thinking of I'm thinking of Henry Miller. I don't write, I don't write big wooly, wonderful books. I write quite spare and a lot of work is editing. Although my original effort on the page. Would come from that process. I do a lot of turning before I go forward. So I make sure what's behind me, whether or not I Jetta sit in it, jettison it in the end. I have to feel like it's in good shape before I move forward, because it will tell me where I'm supposed to go. And if I write a shitty first draft, as they say, I feel like I can just trail off into something ordinary. When if it's honed enough, it can be. Excuse me, it can be it confession a form. That'll take me forward.

Ashley Rindsberg: So at this point in your career where you're, you're on your fifth book and you're able to look back a bit is there anything you would tell your younger, just starting out self at any age, whether you were just starting out with that first novel or before that, you know, and I'm asking this question, I'm asking you what you would tell a younger writer who's grappling with this stuff. Where, how would you guide them? Because to return to how I opened this conversation, it's a difficult, it's a difficult craft. It's difficult in and of itself. It's difficult to do it. Well, it's difficult to leave. By doing it and it's difficult to live with it. I think in a way it's difficult to live with the process of being a writer and a writing and how it affects yourself, how it affects people around you. So within that framework, is there something that you would tell that younger you.

David Francis: I mean, I feel quite emotional when I hear that question. Cause it is, it's such a struggle. And this part of me that would want to recommend don't quit your day job, which was what my first editor in London said, because I thought here I am, you know, it's going to make my life and in a way it did, but then there's another part of me that wants to say quit your day job. Pursue this passion, but it's so scary. And lonely. So I think what I would recommend and I do this, so it's, this isn't really talking to my younger self, but I would recommend finding people in the world who can support this creative part of you. Other writers. Like I would go to readings and then I would make friends with writers and become part of a world. I joined Penn which is a group of writers, so that, and I went to Penn events so that I had a, a support network of people who were experiencing the world in the same way, because there's some, nothing more soul destroying than reading for me reading my first chapter to my family. And just seeing them look at me in the back in Australia, on the farm, look at me, kind of Stony faced and vaguely horrified and, and that, so it's about having support.

And I think being in being with a group, if you can, that you trust that is that is nurturing and you know, that's direct enough and real, I mean, in my group now we're very direct and we go, we cut straight to the chase, but I think to be around people who are creative and nurturing and sort of an artists and finding a world where that can contain the anxieties and the loneliness and the struggle of choosing that path. But I feel like if, if writing is, what, if you're a writer it's, it's kind of what you have to do if you're called to do it, that's what you do. And however you orchestrate it with survival, you know, whether you marry someone who's well healed or. You know, you apply for these fellowships. And I, you know, I was lucky that I got some of those and I felt a bit guilty about getting them because I wasn't a writer in as much financial need, but I was a writer who needed a space and a place and a world where I could explore, explore what I was doing on the page.

So I think there are many ways to skin the cat I would say just to my younger self, as a writer, be kind and be patient. Someone said to me when I published in the UK and elsewhere, she said it'll probably take about five years for you to be published. And I was like, you know, screw that. I'm gonna get, I'll get published before then. And it took five years, you know, it took five years for me to have a publisher in Australia. And then and then also not to have expectations, expectations are the seeds of disappointment and resentment. So just be for me to be where I am on that page, in that scene, and fully realize that without getting into the what's next, who's going to read this, how's it going to get published? What do I have to do? But then also being out in the world where you're meeting people and cross-pollinating and becoming known and doing what you're doing, I mean, doing a blog you know, being, participating in the literary world one way or another is also I think, helpful and not everyone has the ability to do that.

Ashley Rindsberg: Yeah. There's Seth Godin, who is a, a marketing guru who became a philosopher in my mind, who I quote quite often, he said, if you start to organize people in your field, in your area, then the powers that be will take notice, and it can be simple. It can be a writing group, like what you've done with the poetry. Where there's a cluster, that's where it draws energy. It's like a, you know, a heavenly body, the bigger, the more gravity it has. And another thing that I've spoken about here before is this idea called scenious which is the genius of having seen a group of people together, which is something I think Brian Eno coined. Where we see with Andy Warhol, Warhol wasn't Warhol. Warhol was the factory. Warhol was the scene. He was the culture around him. And I think that's very important. I think that's something that. Is connected also to place, you know, and I know that in my case, I here in Israel have not connected with it for whatever reason. And it's, I think it's a big blind spot for me and I can feel it. It's not that it's a blind spot career wise, professionally, which probably it is, but emotionally is the bigger point you miss the gratification of doing what you're doing. If you're not sharing it with other people who are doing it I think that's an excellent point for people to keep in mind.

So, you know, before we wrap up, I want to ask a little more about Penn. Very important organization. There are not that many organizations that are standing up for the rights and the freedoms of writers around the world. It's certainly the sort of doing it in the par excellence fashion during the best, the best way that anyone does that.

How can people support Penn? How can we support writers who are being detained, who are being muzzled, who are being abused and oppressed, because it's hard for most of us to imagine people listening to this, it's almost impossible to imagine, but it's a very regular occurrence in many places around the world. It's sort of the default. If you speak out of turn, as writers are known to do you face reprisals and consequences. So how can we support Penn? How do we get involved? How do we learn? How do we get involved with that mission?

David Francis: Yeah, we forget what a luxury it is to be able to just sit in our spaces and write what we want to, how we want to disseminate that, how we want to. And so it's so easy to forget that there are right as in parts of the world that are being persecuted for what they write journalists. You know, you think about the number of journalists in Mexico who have been assassinated. And now, you know, these writers, women writers in Afghanistan under that new regime and you know, we have on the board a penn international a writer from Myanmar who was in prison for five years. Our new Penn International president is a guy called Burhan Sonmez, who is published in 27 languages or something.

And is Kurdish that lives in Turkey is actually is now at Cambridge, but he, he was tortured by the, the Turks. So part of his work as a Kurdish writer, so that there, there are these risks that are involvedas writers and writers do have some privilege. I think it's it behooves us to, be aware of them and then support them and support freedom of expression generally. So it's totally easy to sign up onto the Penn international website or the Panamerica website. Penn international, overseas, 150 Penn centers all around the world in some indigenous languages and In troubled parts of the world and in other parts of the world. So go to the website, see how you can donate. You can become a, a writer. You can join the writer circle for a certain amount of donations. A certain level of donation. There are all sorts of opportunities to be supportive in your local pen set or wherever you are in the world. And in through Penn international, which is the main center of the organization out of London.

Ashley Rindsberg: It's amazing. I personally will do it in pen Israel. And I encourage everybody else to do the same. And even if you don't have the ability to donate right now, just go check out the website and get on Twitter and find those writers. I just wrote a piece about Nicaragua. Where journalists are being thrown into prison left, right and center by the, by the Sandinistas who had freed that country from the former dictatorship. And now just to become a copy paste version of that, of the thing that they despised it's all around us. So it's something we absolutely need to pay attention to. It feels like it's a bygone. It's something, a Relic from a bygone era. It's absolutely not. The stuff happens every single day. So thank you for that. So where can we find you online or anywhere else in the real world, if that's where we should find

David Francis: Have a little bit retreated from the real world. I do have a website, David Francis here. Dot com I'm on Instagram at and tapered Francis writer. But I've retreated from that somewhat. I'll probably get eaten up again as I have a new book out and get more immersed in that world, but feel free to contact me through my website if you would choose if you so choose. And I'm happy, to make contact and happy to discuss any of this or with writers and work with writers in, in ways of getting into that fibid continuous dream as I call it and or to edit and chat and be part of the global community of writers.

Ashley Rindsberg: That's an amazing offer. So thank you, David. I'm sure some, some of the listeners will take you up. And last question, which of your books do you think is the best entry point into your work, which is the most what you would recommend is someone who's just starting out reading you?

David Francis: I would say "Wedding Bush Road", which was my last book might be the most accessible." The Great Inland Sea" the first book is. A little more challenging in some ways. Not that's a bad thing. And, and then the straight up winter is a sort of literary suspense novel. So it depends what they're drawn to. I would just check them out and see what resonates.

Ashley Rindsberg: Thank you very much David, it has been a great conversation. I've taken away a lot from it and I hope to stayin touch.

David Francis: Thank you, it's a pleasure Ashley. Thank you

Join the conversation.