Courtesy of Avraham Cornfeld.

Avraham Cornfeld is one of Israel’s leading typographers. He’s founder of type foundry Alef Alef Alef and formerly ran Israeli design magazine, Untitled.

Ashley: Let’s start with a little background about you and what you do now. Talk about Aleph Aleph Aleph, your profession and what it means to you.

Avraham: I was born to an Orthodox Jewish family in the Old City of Jerusalem. There are eight of us siblings. When I was about 13 my parents split, the kids went with my mother and we became chozer b’sheala [the Hebrew term for turning from a religious life to a secular one].

That gave me perspective. I came into the “un-Orthodox” world as an observer. I had to observe codes, like what kinds of jeans you’re supposed to wear and what does that say about you. But I also had all the excitement of entering a new and open world where anything’s possible.

But after a few years, I felt something’s missing. I used to always have meaning in every part of life and suddenly there was no meaning to anything. For example, you eat because you’re hungry or you want something yummy. Now what? You’re always chasing something exciting or something that will make you feel good or make you happy.

The result was that all through my high school years, I felt really there was no meaning. I had a big crisis.

Ashley: How did that crisis materialize?

Avraham: I was depressed and I had a few suicide attempts. And I was a really confused teenager. There was some drugs and smoking and alcohol. Then I realized there was something I always liked doing, and that was taking pictures.

That was because my dad, who was chozer b’tshuvah [someone who has become religious]. When he was in his 20s he had a major bike accident and was in a coma for two months. When he woke up he decided he wanted to go to Israel and get closer to God. But until then he was a very creative man.

Growing up with a dad who was very creative, I learned a lot. He continued to be creative in the Orthodox life — in a way. He started doing ktivat stam [working as a scribe writing religious texts]. And he’d take me with him whenever he went to take photos.

I went to study photography and suddenly I found something I was really good at and that could fulfill me.

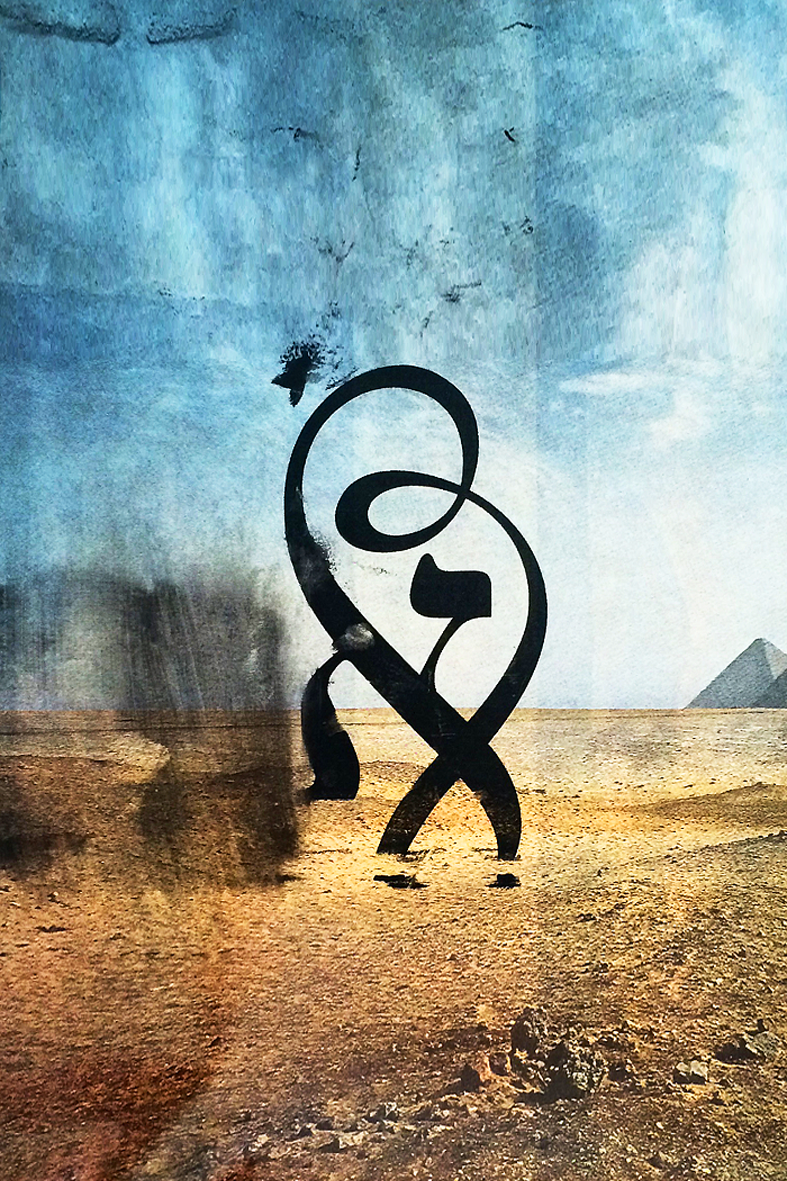

Courtesy of Avraham Cornfeld

Ashley: What about photography specifically lent you to that?

Avraham: Photography is a really expressive medium. I would go out shooting and if I saw something that I related to, for example, something that felt sad, like an abandoned house, I could identify with with. It was like therapy. Suddenly, I felt my sense of abandonment was okay because I was in an abandoned place. But if you go to a party and you feel abandoned you feel something’s wrong with you.

Ashley: This was before digital photography?

Avraham: This was exactly at the rise of digital, around 2006. I was shooting both film and digital. But I liked photography as a form of expression, not as a career or profession. At the same time I realized I liked doing graphic design, and that I’m good at it. So I went to study at Shenkar [the renowned Israeli college of engineering design and art outside of Tel Aviv] where I started creating fonts.

Ashley: Why fonts?

Avraham: When you study graphic design, typography is like 80% of what you do. And a lot of the time I’d create a work and felt there wasn’t the write font out there for it.

I’d create a poster and I’d want the letter to be a certain way – a kind of geometry, or roundness. So in the beginning I’d take existing fonts and I adjusted them.

I have a quality that I need things to be perfect. I appreciate when things are fine and precise. A lot of it is intuition and gut feeling

Ashley: What would it feel like if you put a font on that poster which didn’t belong there?

Avraham: I have a quality that I need things to be perfect. I appreciate when things are fine and precise.

A lot of it is intuition and gut feeling. But a lot is contrast. You take two colors and you try to match them. It has to feel good. But usually colors will match, if there’s contrast.

Also there’s style that’s connected to trend. You’re used to seeing the world a certain way, in some shapes and colors, like when you’re matching something that is warm and something that’s cold, a warm color and cold color. Or a masculine shape with a feminine shape. We’re used to it from nature. It’s a composition.

Ashley: What did you do after Shenkar?

Avraham: I decided after 6 years of study I need a sabbatical. I’m a workaholic. I worked 16 hours a day and when I stopped working I’d basically go to sleep. It’s part of the religious background and part my nature.

When I grew up I wasn’t successful at anything. In school there were the funny kids, handsome kids and smart kids. I was nothing exceptional in any field. So when I went to work in a Dunkin’ Donuts in Jerusalem and I had a chance to be good at it, I went into it fully.

Ashley: You did that?

Avraham: Yeah, I was a shift manager at a Dunkin Donuts in Jerusalem.

Ashley: So in your seventh year you rested. Very biblical. What did you do during the sabbatical?

Avraham: I started to connect to nature, to the earth, on Moshav Herut [in Israel’s central Sharon region]. I had a girlfriend and we lived near an avocado grove. I grew corn and worked on the side. Eventually, I decided I’d take five fonts I’d made in school that had the most potential. I sat and worked until they were finished, until they were good.

I then reached out to some other typographers and with them I created Aleph Aleph Aleph. I’m into groups. Before Shenkar, I created with a friend Untitled magazine, which was a magazine about design and arts in Israel.

Ashley: What brought you guys together around that magazine? Was there an ideology or you just wanted to see each other and talk?

Avraham: I just wanted there to be a place in Israel where people could come together to talk about design. And there wasn’t one. So I created it. But that meant when I started Aleph Aleph Aleph I already knew a lot of people.

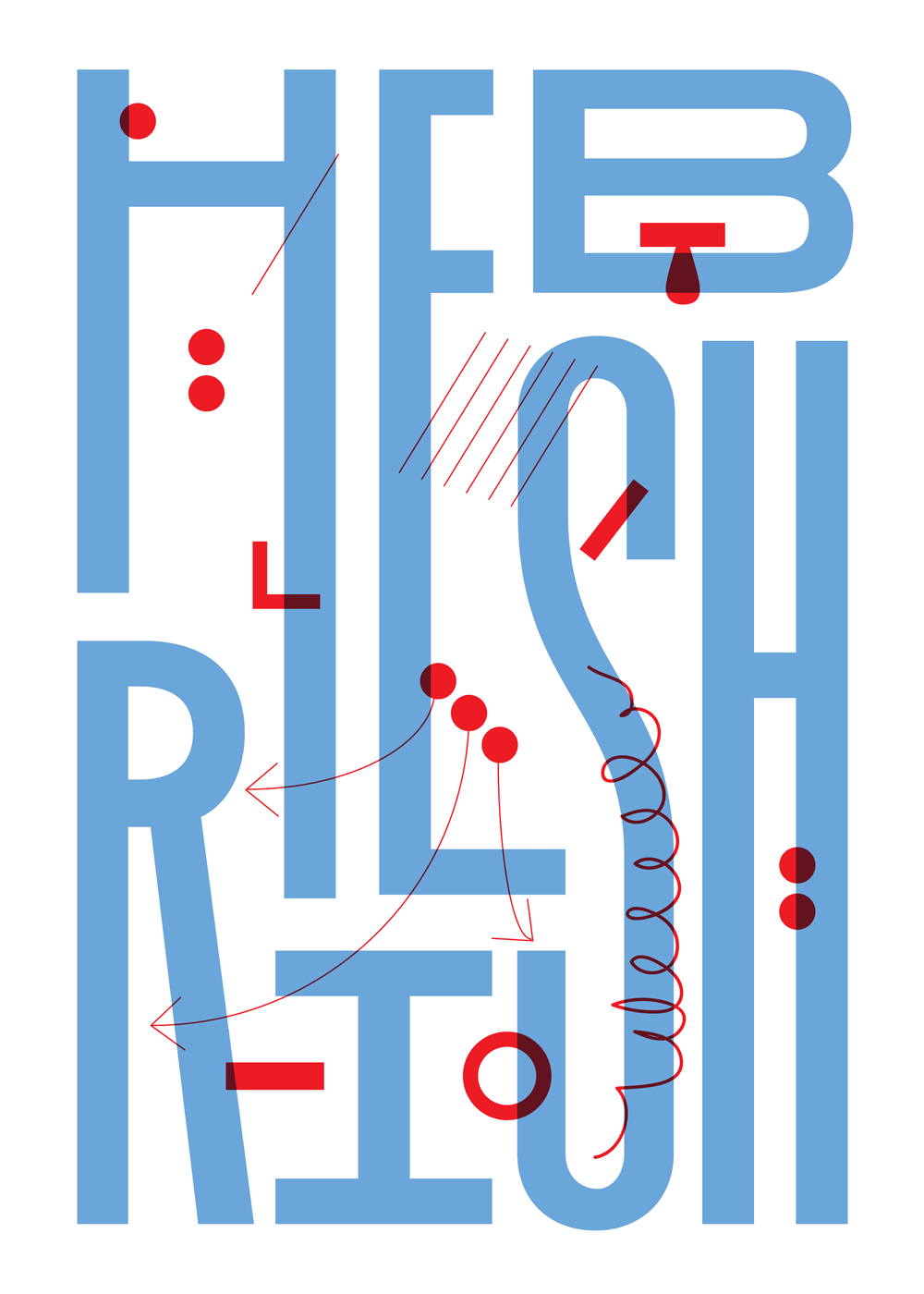

Courtesy of Avraham Cornfeld.

Ashley: Where did the name come from?

Avraham: One night lying in bed I imagined a site full of alephs [Aleph is the first letter of the Hebrew alphabet]. You’d come to the homepage and see a bunch of big alephs and you’d click an aleph and see that font.

People told me not to do it, since in Israel the connotation is not so good. That’s because people would put Aleph Aleph Aleph in front of the name of their business so they’d appear first in the yellow pages.

Ashley: That’s so Israeli. So why did you say, screw it I’m doing it anyways?

Avraham: That happens a lot with me. Sometimes I know what I’m looking for. In that case, I felt like people didn’t understand what I understood. I felt that all the clients I’d be aiming for would get the joke. They’d know that this wasn’t me being one of those yellow pages companies.

Ashley: It’s a pass-key, like the word Shibboleth from the Torah.

Avraham: Yeah, exactly. And as a joke we designed fliers for cheap companies, like the ones plumbers put in your mail box. That’s the joke of Alef Alef Alef.

Ashley: And you were doing the exact opposite.

Avraham: Yes. We created all this junky design and a lot of people didn’t get the joke. We’d get these messages on Facebook saying your work has really gone downhill.

Ashley: There was a meta-language.

Avraham: Yeah. And in typography that matters because a lot of designers don’t really know if it’s a good font or not. It’s like in fashion. People need to see the celebs wearing your clothes and then they’ll wear it. A lot of people don’t really have good taste. But if you got the joke, you’re a good designer.

Ashley: So what’s the project for you? You care about the fonts. You care about how they’re used. What’s the bigger aim? A lot of people would say, “Great, I’m selling more and more fonts.” But you want something else. What is that?

I want to leave a mark. It gives me nachas [joy] to see my fonts used in a way that makes the world a nicer and more aesthetic place.

Avraham: I want to leave a mark. I’m very connected to my fonts. Each one I spend many weeks and months, even years, and it gives me nachas [joy] to see them used in a good way, that looks good, and that makes the world a nicer and more aesthetic place. And when I see them used in a bad way you feel there was no need to design a font for that. It’s like they’re grinding the font like bad drivers do to the gearbox of a manual-shift car.

Ashley: I think it’s something a lot of creators deal with. Like screenwriters who write something and then have other people make the movie. I think that’s common to a lot of creators. It’s like having children. You want to send your kids to a good school, not a bad one. But the question is how much can I hold on? I did my best as a parent and now I have to let go.

Avraham: It’s hard. I think it’s similar to writing, but it’s almost more like music. You make a song and someone re-mixes it.

Ashley: Where do you see Israeli design today? Where’s it going?

Avraham: People are designing more and more in English. Our Hebrew language is very unique but if it goes on like this in a few years everything will be in English - every product, every coffee shop, every fashion label in Israel will be in English because it looks international.

Ashley: Is there any force resisting that trend? Are there designers or creators of culture saying, “Let’s return to our roots?”

Avraham: Very few, but there are. A lot of them are in Jerusalem.

Courtesy of Avraham Cornfeld.

Ashley: What’s your view on the future?

Avraham: I’m a futurist. I like to think about what’s next. I believe we’re at the top of this technology cycle. The next thing will be very exciting, and will change the world.

Ashley: And what’s your advice for young designers today?

Avraham: My advice to designers looking to build a career is to go into hi-tech. But if it’s a designer who wants to be remembered for doing something meaningful, they should do their own thing. There’s a saying, either you make your dreams come true or you work to make someone else’s dreams come true.

People who have something to say to the world should create their own thing.

Ashley: It’s about finding the next thing, not following the next thing.

Avraham: Exactly.

Courtesy of Avraham Cornfeld.

Join the conversation.