Courtesy of Amelia Green-Dove.

Amelia Green-Dove is an LA-based documentary filmmaker. She is the producer of award-winning documentary film “Watchers of the Sky” and has served as archival producer on numerous films, including “Take Every Wave: The Life of Laird Hamilton” and “Without a Net: The Digital Divide in America” and “Above and Beyond: NASA’s Journey to Tomorrow.” Amelia is currently producing a documentary about iconic Southern California surf-rock band, Sublime.

Listen to the episode on your favorite podcast site:

Apple Podcast: https://apple.co/3nbH6b1

Spotify: https://spoti.fi/3K8GcpF

Amazon Music: https://amzn.to/3n7753h

iHeartRadio:https://ihr.fm/3J3W2kT

Ashley: Amelia, tell us who you are and all the various things you do.

Amelia: I'm primarily a documentary filmmaker. I have a background in journalism, but it’s all in documentary and that kind of broadcast media. I also write and am dipping my toes into narrative, meaning non-fiction filmmaking. And I collaborate with Yaron, my partner, on some of his art projects, kind of from a producing side of things.

Ashley: How did you get to documentary filmmaking? And what keeps you doing it? I’m assuming it's probably not the easiest thing to do in life.

Amelia: No, it’s certainly not the easiest thing to do. I initially got into it because both my parents were in the film industry. My mother was a sound editor and my father is a feature film editor who did big Hollywood romantic comedies. I grew up going to Disney Studios and the Sony lot and Paramount. I was always visiting the backlots and the cutting room and going on set to see actors working and all that kind of stuff.

But my parents were very politically aware and active, my mother especially. She was active in the union and in the kind of politics that were happening in America and the UK. (She was British.) So I felt like I knew that world and I liked it. But I didn’t want to do what my parents did. I wanted to do my own thing.

By Coolcaesar at the English language Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=15740739

Ashley: That makes sense. So what was the next step for you?

Amelia: I realized there actually is a form of film where you can marry your political interests and social interests with filmmaking and that’s documentary filmmaking. Especially for women, who might find it hard to breakthrough to the top levels of the feature film world, documentaries are really a good home. And not just for women but I also think for people of color. Documentary filmmaking offers a path forward because you can raise a couple of hundred thousand dollars to make a documentary without having to pull together millions for a Marvel movie.

There’s a rich diversity of voices today. And the industry is changing in that regard.

Ashley: That’s a great point. It lowers the barrier to entry for creative people trying to work in a very difficult industry.

Amelia: Exactly. There’s a rich diversity of voices today. And the industry is changing in that regard, though less so in the feature film world. But also the way we work matters to me. Documentaries have small crews so when you’re starting out so you get to do everything. You can see every kind of line of work, which is really interesting. And it gives you access to the full experience of making a film. Whereas if you were on a big feature film you have your narrow little lane.

Ashley: How did you get your start in the business?

Amelia: After college I got an internship an at the BBC briefly in London and from there I moved into a low-level job on Bill Moyers’s program at PBS in New York. I worked my way up on Bill Moyers’s show until I was an associate producer on the program.

Ashley: How was working at “the Beeb”?

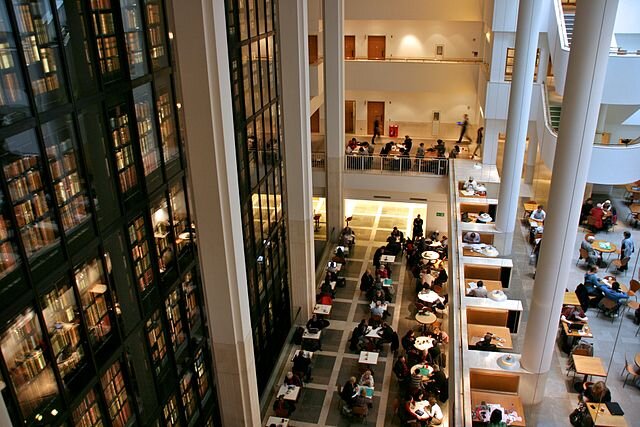

Amelia: It was great. I was interning on a multi-part series called “The Trouble with Love.” As part of my job, I had to go to the British Library to do research, which was amazing

Ashley: I love the British Library. It’s a reader’s paradise.

Amelia: Well the really amazing thing is because it's the BBC they very quickly pulled the strings and got me access to the reading rooms. I was in college and suddenly I’m handling these 15th century manuscripts. It actually set me on the path to do archival producing, which is what I do when I'm not producing my own projects. That's also been a thread throughout kind of my professional life, doing archival stuff

Ashley: What does that mean exactly?

Amelia: It means basically overseeing all the non-original footage in a documentary. So some documentaries just have a few old photos but more and more documentaries are using archival footage, sometimes up to 90% of the film is not footage the filmmakers shot themselves. It can be old film footage but it can also be photos, or audio, or whatever you can get your hands on.

The British Library in London. Photograph by Mike Peel (www.mikepeel.net). / CC BY-SA (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)

Ashley: It’s like “The Kid Stays In the Picture.” To an outsider, the movie felt revolutionary. Like they did this whole new thing.

Amelia: They did a really interesting treatment of the archival footage in that film. More recently, there was the Amy Winehouse documentary, “Amy.” If I’m remembering correctly that was all archival, virtually 100%. They did their own interviews but they were audio interviews. So you're hearing the interviews but you’re not seeing any interviews your just seeing beautiful amazing archival footage.

At the end of the day, when you’re dealing with a film story trumps everything.

Ashley: I love that. So how did you get from there to the Sublime project you’re working on now?

Amelia: You know what the weird thing is – and maybe this isn’t that strange – but I find that the film industry it’s all word of mouth. Nobody has ever asked to see my resumé. Just about everything I've ever done has in some way has been connected to Bill Moyers. It was just an amazing group of people working on the program. And all those people have since left and done interesting things. You could probably trace 90% of the projects I've done back to somebody involved in that first project.

So, I would guess there was probably some sort of Bill Moyers connection that led me to the Sublime film.

You have to service the story and if you lose sight of that or forget that you end up with a really boring film or a film that doesn’t make sense or a film that’s not as powerful as it could be.

Ashley: Where do you go to find material for a project like that? For certain other projects you can imagine the British Library is a natural step. But how do you go about finding that kind of footage for a band that hit in the 1990s?

Amelia: That’s all about taking to people. It’s about picking up the phone and having conversations, and working to get people to trust you so they introduce you to other people. You visit their homes and go through their garage with them, rummaging through old boxes and finding old photos. In this case, it was a lot of driving around Long Beach and Orange County.

Ashley: Listening to Sublime…

Amelia: Yeah, I actually did listen to Sublime as I went to visit people. There are also some amazing hardcore collectors of not just Sublime memorabilia but photographs and original lyrics and they were either friends of the band or they were just people who since then just love the band and have made it their business to collect material.

Ashley: I imagine part of the magic is that you like uncovering these nuggets. Once they’re discovered, it gives someone an opportunity to save that material, to recover it.

Amelia: That is definitely true. What’s interesting about working on a film as opposed to, say, just building an archive is, at the end of the day, when you’re dealing with a film the story trumps everything. As it should. You don’t want to watch a film that’s just amazing archives strung together, as interesting as that might be for the nerds among us. I could watch that all day. But in a film you really want the story to trump everything. What I always find really interesting is that sometimes you discover these amazing gems, something never been seen before, a new film transfer of amazing material, and it’s just incredible. But it doesn’t make the cut. It doesn’t end up in the film and that’s because it just doesn’t need to be there. Because the story is the most important thing. You have to service the story and if you lose sight of that or forget that you end up with a really boring film or a film that doesn’t make sense or a film that’s not as powerful as it could be.

Ashley: Kill your darlings, as they say. Even though I hate that saying, because it actually hurts every time. Though at some point it's like you become a serial killer of darlings and then it stops hurting so much and you’re like, “Whatever,” just another dead darling.

Amelia: It’s also the advantage of having an editor, both in writing but also in a film. I probably get this from my father who did these big Hollywood films but never liked to schmooze with the actors. He really respected the actors but he felt like if he was going to do right by them he couldn’t edit them as their friend. He couldn’t find himself saying, “I love when the actor did this or that. I’ve got to include it because he or she will be so happy to have that amazing performance in the film.”

Instead, he just had to be brutal, he’d say to himself, “I don’t care how hard you worked for that shot. I don’t care how hard that was to film. I’m just going to cut it if it’s not working.” And you sometimes need that outside person to say that. It’s the same with documentaries. You need an editor who’s like, “You know how rare that footage is. Congrats. Wonderful. That’s really rare footage. You dealt with someone who didn’t want to give it to you and you convinced them to give it you. Here’s a gold star. I'm not going to use it. It doesn’t make sense for the project and I'm not going to use it.” You really need that balance.

Ashley: I think that cuts to the impermanence of any form of creation. There’s always that notion we all carry inside of us that, at some point, the project will be done. Whatever will happen, will happen. And then time will just sweep it away. So, as long as you’ve done the thing you wanted to do to a level that you wanted to do it, then mission accomplished. Move on. And I think that’s where we see really great creators just move onto the next thing.

Amelia: I think that’s true. It’s really a nice feeling when you do that with a film. Just be done. Close that chapter. It's delivered and you literally have your delivery paperwork and then you can not think about it again for 10 years until the rights come up. But the sad part of that, at least in film, is that you develop really tight relationships with people when you're working together on a project and when it ends you move onto a different team. Also, that period of your life when you're working on that one film, it’s not kind of just letting go of the work it’s also letting go of the moment.

Ashley: Letting go of that person that you were for that period of time.

Amelia: Exactly.

Ashley: That’s the hard part of growth. We never want to let go of that previous person we just got to know. And now it's time to say goodbye. There’s something heartrending about it, even when it’s a positive progression. You still want to cling to that thing.

So how do you locate the larger meaning of what you do, such that you’re not just moving from job to job but that it remains something rooted in art?

Amelia: I find that I get meaning from the subjects I choose to work on. I spend a lot of energy making sure I'm choosing the right projects because it is such a commitment of time and energy. I choose things I feel like it’s going to allow me to explore really interesting things or because I know that the final product is going to be something I'm really proud of.

I worked on a documentary for almost six years maybe even a little bit more called “Watchers of the Sky” about Raphael Lemkin, who coined the term “genocide” and it was also about people today who are continuing his work and I produced it and it was a really, really tough project to produce for a variety of reasons

Archival image from “Watchers of the Sky” (Courtesy of Amelia Green-Dove)

It was a really tough project to make and we were really lucky that it went to Sundance, it sold, won awards at film festivals, including at the Jerusalem Film Festival. And I still get emails about it once or twice a month. Somebody reaches out and says, “I love this film. I’m a teacher in Texas who’s teaching the Holocaust or genocide to my class and I showed the film to my students who thought it was amazing.”

Ashley: What do you see for yourself on the horizon? Do you keep moving to different projects as a producer or do you want to do something different?

Amelia: I love producing. I really do. Because I love taking helping somebody who has a vision help them make it a reality. I find that very rewarding. I like what’s called creative producing, meaning it’s not line producing, which is about overseeing the budget and the logistics, though I do that too.

I get what you’re going for but that’s not on the page. That was just in your head.

Creative producing is more about sitting with a director and helping them figure out what they’re thinking. It's like being an editor, in terms of a literary editor who helps take somebody's raw creative spirit and shape it. So, hopefully I will get to continue doing that going forward.

Ashley: It sounds like a great role to be able to play. I think the creator on the other side of that chair facing you can tend to be really wrapped up in their own project and in their own notions of the project’s success and failure. The stakes can become disproportionally high and often a sense of isolation kicks in.

I feel like with those editors – and I know one in particular who’s helped me for a long time on a book I just finished – there’s like such a level of selflessness in the moment.

Amelia: I find that being on the other side of that table is so rewarding because you can hear that raw thought process. But when it’s in your own head it can be hard to see the path forward. When you're on the outside and someone’s coming at you with all these raw ideas you say, “I see what you're going for.” I know when I sometimes read Yaron’s writing I'll note something I didn’t understand. He’ll try explain it and my response is often, “I get what you’re going for but that’s not on the page. That was just in your head.”

Ashley: It’s a fascinating relationship. Those two people, the editor and the creator, can’t exist without the other. But it’s a mutualism, not a dependency in a negative sense.

Amelia: It’s all about the story, at least when it comes to filmmaking. It doesn’t matter if you’re the director or the writer or the editor or an actor. It’s a team effort and you’re all working in service of the story.

Ashley: I feel like we’re seeing the effect of that service-of-the-story effect from film in the world of literature. There’s a sort of downward pressure on writers to change the way they go about writing. It’s not enough to write an amazing highly stylized sentence-by-sentence novel or story. It’s just not going to cut it. Audiences today are so exposed to high-level storytelling that they have to think differently about story.

Amelia: That’s interesting. I think at the end of the day ultimately you want to feel something.

Ashley: One more question, this one coronavirus-related, which is about maintaining productivity as a working creative person who is also a parent.

Amelia: That it is forever a challenge. Our one-and-a-half year old son is not yet in preschool or daycare so it’s a lot of juggling. Yaron and I have time for each of our individual projects but it never feels like enough time. But spending time as a family is the most important thing and also something you really have to prioritize otherwise it just won’t happen.

Ashley: Amelia, thank you for doing this. It was really great and generous of you.

Amelia: It's been really interesting. Thank you.

Join the conversation.